Published Sep 12, 2023

How Voyager, Janeway, and Star Trek Pushed Science Fiction into Bold New Directions

A case study exploring the changes in storytelling and the impact of the presence of women leadership in Star Trek.

StarTrek.com

Before earning her Ph.D, Dr. Leigh McKagen pondered what her research would look like. A Virginia Tech graduate twice over (in 2006 and 2009), Dr. McKagen was teaching at her alma mater and was mentally working herself into the right state of mind to go for the doctorate. Her problem was settling a subject for her dissertation from the world of culture, politics, history, and ethics.

One evening, after putting their daughter to bed, Dr. McKagen’s husband invited her to watch an episode of with him. This was fortuitous, as she had been considering looking at American Science Fiction as a subject. Before she knew it, the long time science fiction fan had been sucked in by TNG, and soon , watching two and three shows a day — logging every single episode over a year and a half.

StarTrek.com

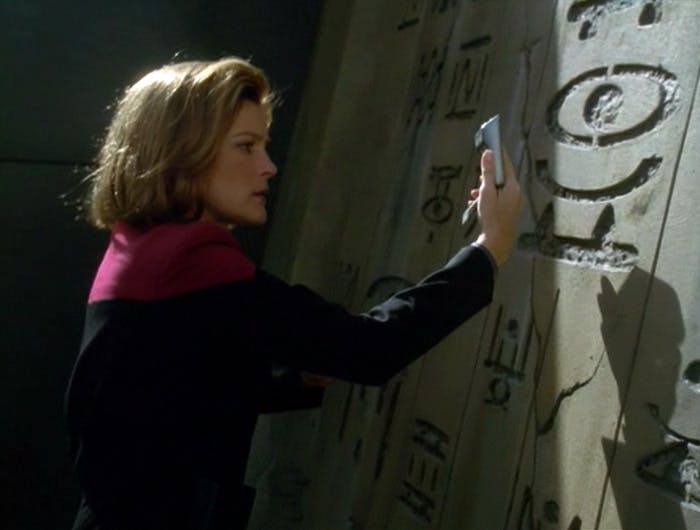

She found Picard to be an amazing leader, but it was Janeway who really piqued her interest. She dove headfirst into the world of the U.S.S. Voyager and its adventures in the Delta Quadrant, and how those stories reflected a style of storytelling that can trace its roots from Gulliver’s Travels to Gunsmoke. Even without knowing it, Janeway and her crew were a part of an imperial saga, told by the Spanish, French, English, and yes, Americans, to justify conquest.

In between teaching at Virginia Tech, raising her three-year-old, giving birth to a baby boy, and through the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. McKagen wrote her masterpiece, which looks at the cultural significance of Star Trek: Voyager, and how the show and its star, Kate Mulgrew, both pushed the boundaries of what had been done for women characters in the role as leader within the boundaries of the genre of American Science Fiction.

StarTrek.com: Tell us about your project.

Dr. Leigh McKagen: My dissertation is a case study, essentially, of Star Trek: Voyager, and the various ways that European Imperialism and imperial ideologies and practices are written into the narrative. This happens in a number of ways, including the reliance on castaway and adventure narratives that serve to establish the right of the explorer in the way of American settler colonialism.

I explore the way that Voyager taps into the creation of the domestic space-home against the wilds of the frontier of the Delta Quadrant, as one of the many traditions of American imperialism. That was fundamental in the creation of an American empire and an American nation.

Then I ended the project with an exploration of ways that Voyager offers some moments of exception to these imperial narratives. The way to think about how the genre, Star Trek in particular, and American Science Fiction television more broadly, could move beyond that.

The overarching purpose of moving beyond these narratives is the crisis known as the Anthropocene — the Climate Crisis of the 21st Century — that was in large part caused by Western imperialism and capitalism. I’m seeking a way to use this work as a way to not only diagnose the problem, but also see where change could come, or where change could happen within those dominant, and often unacknowledged narratives.

StarTrek.com

StarTrek.com: How did you become interested in using Star Trek for this huge project?

Dr. Leigh McKagen: It sort of happened almost by accident. In terms of general interest in the show, and then we’ll speak academically, they are sort of two separate things. I actually did not watch a lot of Star Trek growing up unlike a lot of academics who work with Star Trek. So I think I come at it sort of from the perspective from writing about it, which puts me in an interesting position. I was familiar with it, and I had seen a few episodes. I knew the pop-culture significance of the series, but I hadn’t really dug into Star Trek. I was very interested in popular culture as a teaching tool.

I started using a lot of science fiction and fantasy TV in my classes. I would show a Buffy the Vampire [Slayer] episode and we would talk about communication. I used those tools as a way to bridge the gap for my students between the academic stuff that they were reading and their real life.

So when I started thinking about a Ph.D. I sat down and talked with [the director of the academic program], and said ‘I want to write a dissertation on science fiction, on science fiction television. I want to explore how this genre engages with America and American culture.’ This particular genre of American television engages with the story that we tell ourselves about what it means to be American.

And then my husband, Branden, said 'Hey, let’s start watching Next Generation!' I said ‘sure.’ I had never really sat down and watched from start to finish. It sounded great.

It didn’t take long of watching it for me, not only to get hooked as a science fiction fan, and also as someone who was working with the genre from an academic standpoint. My original ideas for the dissertation actually involved talking about and tracking 20 years worth of American television.

But my committee said this was really a big project. They encouraged me to cut it down and to pick just one show to work with. It was hard enough to juggle the 172 Voyager episodes, not to mention the many others.

Through all of this, I still was not really sure exactly where I was going to engage with the genre, but I started reading more about imperialism and, in particular, ways that imperialism is still a very much present and ongoing formation and player in not only the global order but also in our daily lives in ways that we often don’t talk about or don’t acknowledge. America has always pushed against the label of being an empire, even though we absolutely always have been, from the early days of settler colonialism.

I was very interested in how that started playing out in these narratives that we tell about the present, as science fiction does, but also about the future, which Star Trek, in particular, really tries to engage with.

StarTrek.com

StarTrek.com: Why did you focus on Voyager, and not The Next Generation or Deep Space Nine?

Dr. Leigh McKagen: In large part, it was a practical decision in picking Voyager, because a lot less people talk about Voyager, which made it seem more manageable for me and also perhaps, more interesting. Everyone wants to talk about The Next Generation because it’s amazing.

Voyager is often a footnote in somebody’s book. I’m reading these books about the myth of Star Trek and even ones that were written in the late '90s and early 2000s, there are only two pages on Voyager. I still really don’t know why people don’t talk about it, but I did, and it was fun.

One of my committee members kept pushing me on [saying], 'you’ve got to think about what was going on in the ‘90s and why Voyager was doing these things and tackling these issues.'

It is very important and interesting to look at the time period in which these shows were being made. I think that Deep Space Nine and Voyager really do reflect the deep uncertainty in the ‘90s, where we — the government and the popular narrative — was really trying to figure out what was going on. In the wake of the dissolution of the Soviet Union and in the wake of the Cold War and the rising Culture Wars, and I hit on this in a couple places… trying to figure out what was really going on. To some degree, those shows are a reflection of that.

StarTrek.com

StarTrek.com: What were some episodes of Star Trek that got away from the “imperialistic” narrative?

Dr. Leigh McKagen: The Next Generation episode that did this best was “.” It’s one of everybody’s favorites; it won a Hugo for very good reason and it’s a phenomenal episode because they lose. Because Picard just lives that life unable to save things; Picard as Kamin, he does not win and they do witness the natural destruction of the planet. Picard has to take that and live with those ideas.

There’s something to be said in studying and exploring those episodes, and Voyager plays with those in a couple of ways. Like “Memorial,” there’s definitely potential there. I think it’s important to note that and I think that is why I really wanted to keep that last chapter, but maybe that’s not the point right now. It’s important to engage in that, even though it’s a minor part or an afterthought of the project in some ways it might seem. But to note when something is going well or perhaps differently in completive ways and more could be done with that.

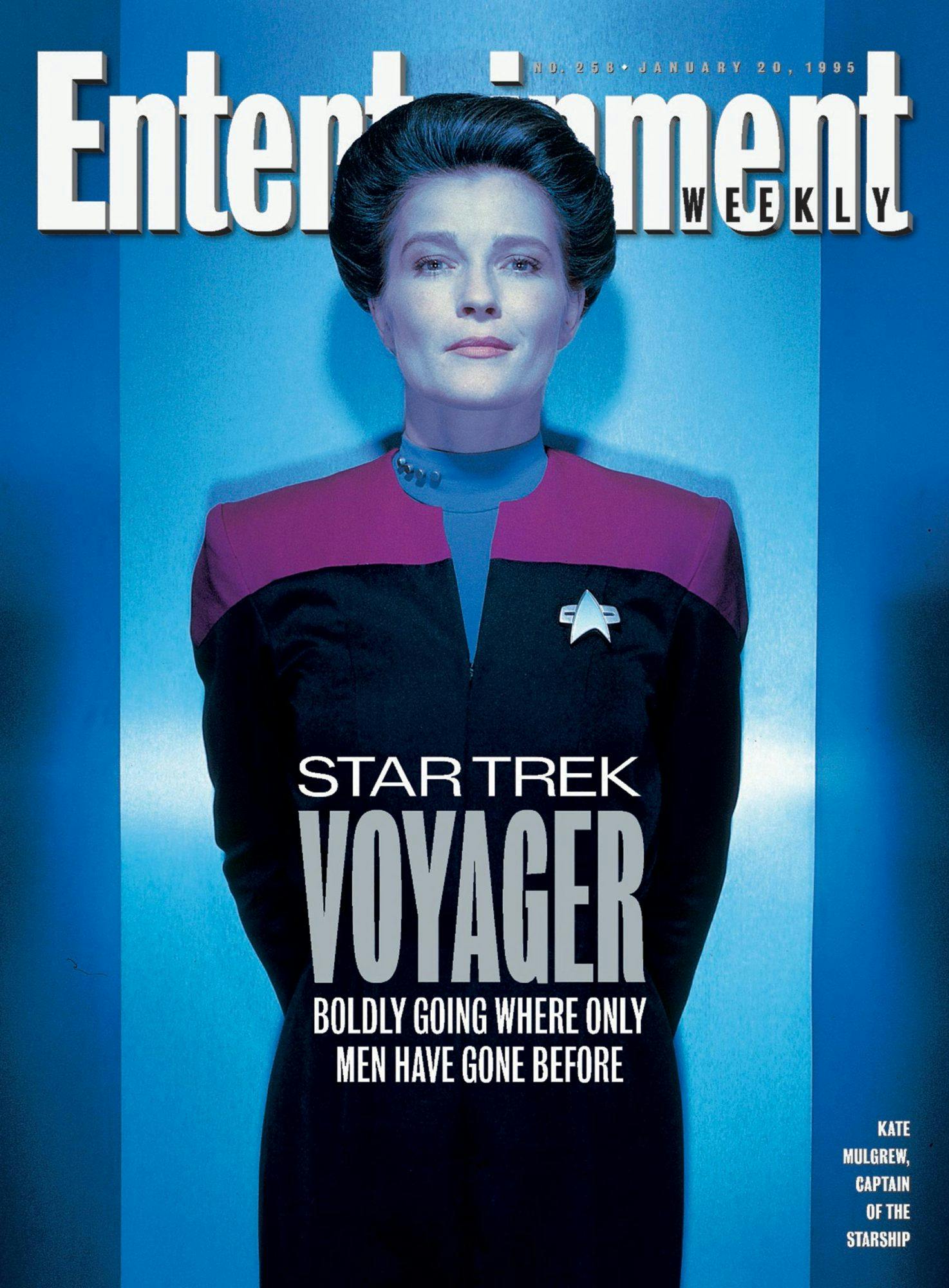

Entertainment Weekly's January 20, 1995 cover featuring Kate Mulgrew as Captain Janeway

Entertainment Weekly

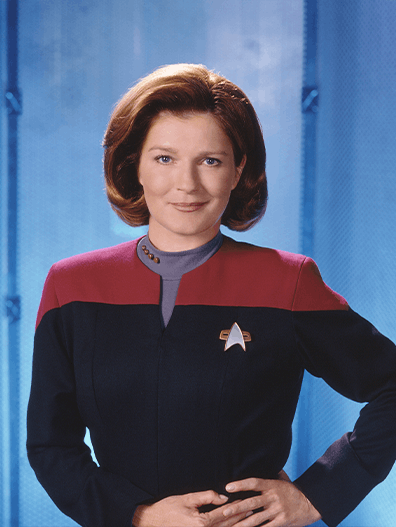

StarTrek.com: Why is Janeway so important?

Dr. Leigh McKagen: There’s a cover of the January 1995 Entertainment Weekly that has Janeway in uniform, which was out right before the series aired as the flagship show of this new network (UPN). And the tag of the cover of the magazine says “boldly going where only men have gone before.” And I think that in a lot of ways, that was really important in the ‘90s. And it continued to be important to me, maybe as a female audience member, but certainly someone who was engaging with the show, even in my 30s, that this is such a male-dominated show up until the ‘90s.

While there’s a lot of Janeway that’s masculine, they at least wanted to engage with that, or straddle that kind of passionate captain in ways that not even Picard isn’t quite able to be.

For me, I think that makes Janeway a more interesting study than someone like Picard or Sisko, who was great, and even Archer. Trying to watch through all these series, all the captains were unique in their own way and they have their own battles to fight, which make each series unique. But Janeway was in the position as being the only woman captain, but being the only woman captain in exile. She can’t just go and get new crewmembers when something isn’t going her way.

She can’t just turn to the Federation for help — not that Picard and others could do that either, but sometimes there were problems with communications or what have you. So she’s very much the solo figure. [At the same time], she’s just such a strong character and always so decisive and really smart. There’s definitely a lot to admire about Janeway.

StarTrek.com

StarTrek.com: What does it mean now that Michael Burnham — an African American woman — is the face of the Star Trek franchise?

Dr. Leigh McKagen: It’s two fold — I think it’s amazing that we also had a second-in-command main character (Burnham), but we also had the captain (Georgiou). The captain and the second-in-command are both women and not white, and I think that those are great things.

I think that there’s some very interesting things happening with , and I look forward to sitting down and watching that series a lot more carefully, and engaging with it as perhaps a follow-up to the things that were happening in the earlier series. In particular, in Voyager, a woman-led show, going where no man has gone before.

StarTrek.com: What could Star Trek do to change the narrative in science fiction?

Dr. Leigh McKagen: That’s someplace that I definitely want to go with my research. The final chapter engages with some of the ways they could have done that. Then I think that if Western Science Fiction, and particularly American Science Fiction will have to move away from the classic “western” approach and shift to stories like AfroFuturism and other alternatives. That’s ultimately what I’d like to see.

Some of the ideas from Ursula K. Le Guin, who's such an amazing science fiction author, and the ideas of thinking about stories that don’t have to have a beginning, middle, and end. Where you don’t have to triumph over something or return home. What would have happened if the Voyager story ended like it did with "" did in that one episode. It would have been depressing, sure, but substantially more realistic in the long run.

In order to move beyond the “hero-journey,” which is very imperialistic, we must ditch the hero. If anybody could do it, then I think it could be Star Trek and that would have a whole lot of power.