Published Sep 25, 2024

William Ware Theiss: The Man Behind Star Trek's Space Couture

Star Trek's fashion is universally recognized, now get to know the man who pioneered them.

StarTrek.com

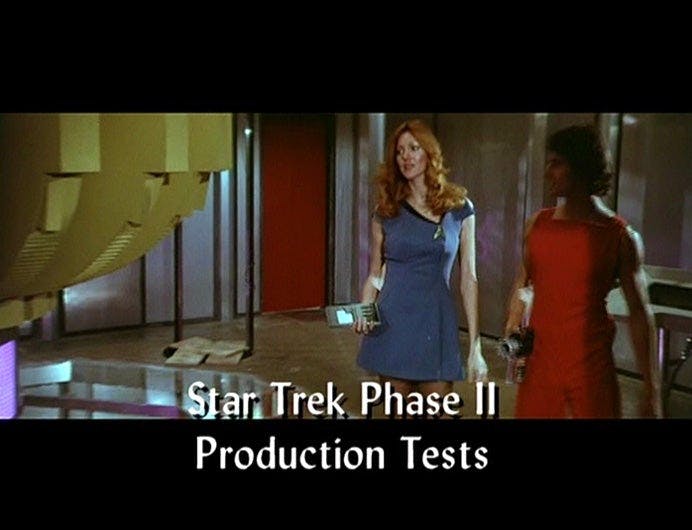

"In early 1988, I wrote William Theiss a fan letter. At the time, I was trying to duplicate the TNG uniforms, so I included a few questions about the materials and construction of the studio costumes," says Dennis Russell Bailey, one of the writers of 's episode "."

"To my complete surprise, he called me a week later at what would have been about six [in the morning] Los Angeles time. He began by saying 'I don't write replies to fan mail, but if the letter is fairly intelligent sometimes I call.'"

"The Big Goodbye"

StarTrek.com

The Star Trek designs of William Ware Theiss are legendary. His uniforms for and The Next Generation are so iconic that they've become visual shorthand for science fiction. Everyone knows these costumes, even if they're not Star Trek fans.

While the works are famous, their creator is something of an enigma, largely unknown even to longtime fans. He was a private man, giving few interviews. As a gay man in the early days of gay liberation and then in the era of the AIDS crisis, he may have been circumspect in regards to how fans and the public saw him. Let's piece together his life and career to get a brief but cohesive look at Starfleet's first fashion stylist.

Early Voyages

StarTrek.com

William Ware "Bill" Theiss was born on November 20, 1931 in Medford, MA, to Harold H. Theiss, an engineer, and Helen H. Theiss (Freeman). The family resided in the Boston area until 1941, relocating to Bremerton, WA, for the duration of World War II.

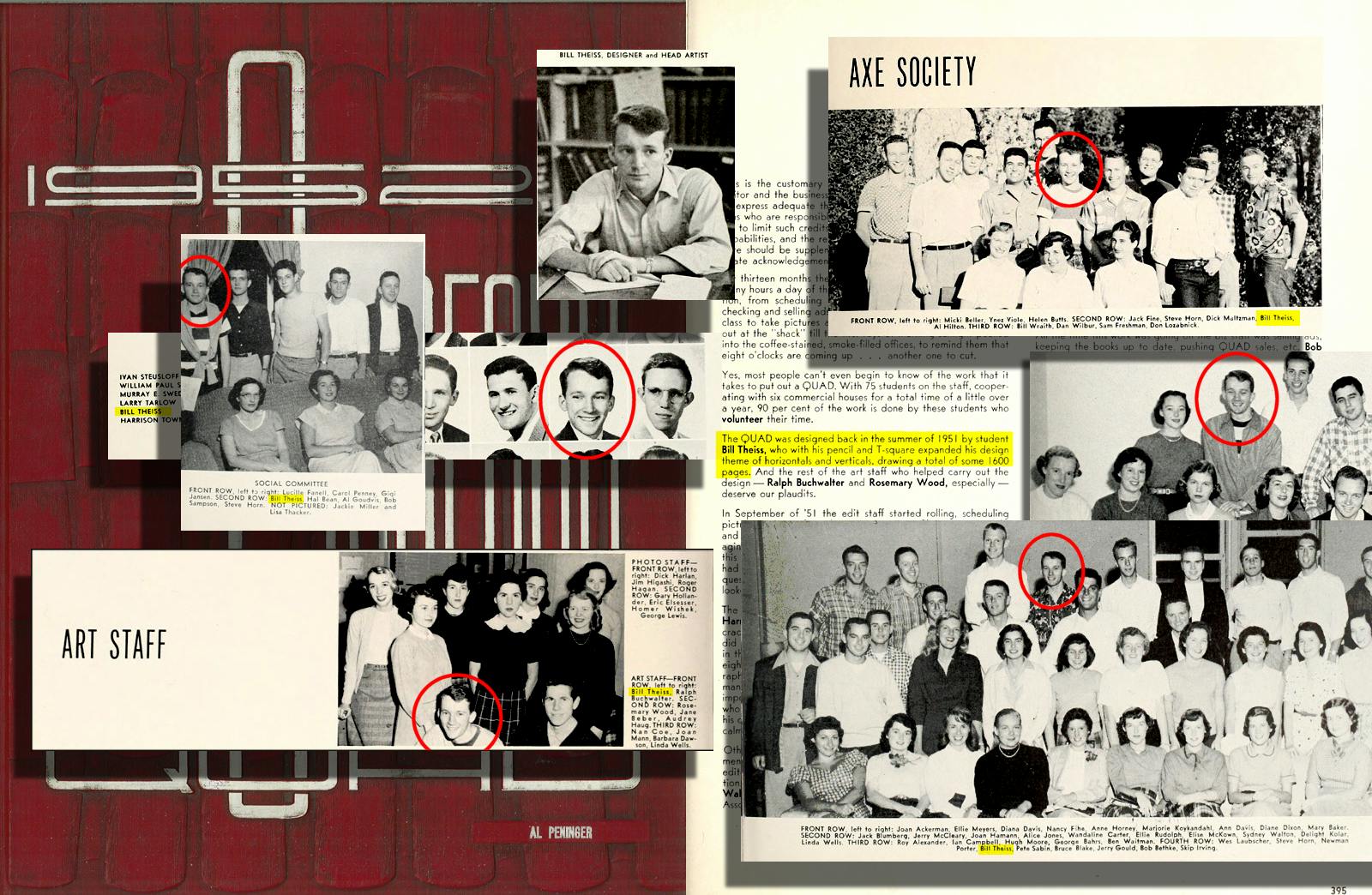

Upon graduating from Lowell in 1948, Bill attended Stanford University, emerging in 1952 with a Bachelor of Arts as an art major with minors in sciences, biology, and chemistry. He was the designer and head artist for the 1952 Stanford Quad yearbook.

Four years in the U.S. Navy followed, with Theiss primarily stationed at Treasure Island at San Francisco, and a year in the Pacific, stationed at Kwajalein, during which he witnessed hydrogen bomb tests at Bikini Atoll.

Following his discharge, Theiss made a brief, failed attempt to be an artist in New York. "I was not really good enough, so decided to go back to school," Theiss said in the 1968 interview "Behind the Camera" for the Inside Star Trek newsletter. So he attended Art Center in Pasadena, California. His first Hollywood job was six months as an apprentice artist in the Advertising Art Department at Revue Studios (Universal). He then started work at CBS, in charge of the wardrobe department for two half-hour "soaps," Full Circle and Clear Horizon.

StarTrek.com

In late 1959, while doing uncredited wardrobe work on pickups for Stanley Kubrick's Spartacus, Theiss was introduced to a young "smart aleck" member of the typing pool named Dorothy Fontana (who provided many quotes for this article via the email correspondence we shared during her life). The two quickly became friends and would remain so for the rest of his life.

With work slow, Theiss skipped off to Europe to work wardrobe on the films, Island of Love and America America, and The Pink Panther, credited as "wardrobe consultant," but The Los Angeles Times later reported him to have created "fashion designs" for actress/model Capucine.

Trek into the Fantastic

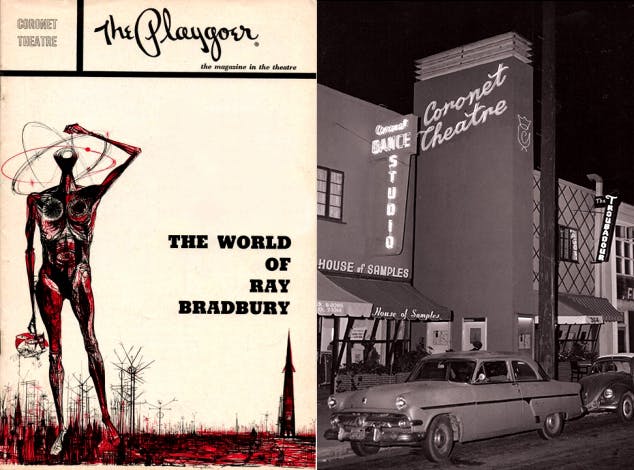

The World of Ray Bradbury playbill designed by Joseph Mugnaini and the Coronet Theater

Coronet Theatre

Returning to Hollywood, Theiss' first foray into the fantastic was My Favorite Martian, which led to a job as costume designer for science fiction legend Ray Bradbury's stage production The World of Ray Bradbury, three one-act plays which included an adaptation of the short story "The Veldt." Theiss recalled it offered him "a marvelous opportunity to do lavish futuristic costumes appropriate for the time and setting of the 1990s."

In his review of the production, Frederick Patten of the Los Angeles Science Fantasy Society (LASFS) singled out "The Veldt," writing, "The result was quite interesting; the basic designs were not too unlike current styles, but just enough different in material and cut to call your attention to them.... George Hadley's neon-blue necktie and Lydia's fur skirt were the standout pieces to me."

The October 1964 play was the turning point in Theiss' career because his "smart aleck" friend Dorothy talked it up to her new boss — Gene Roddenberry.

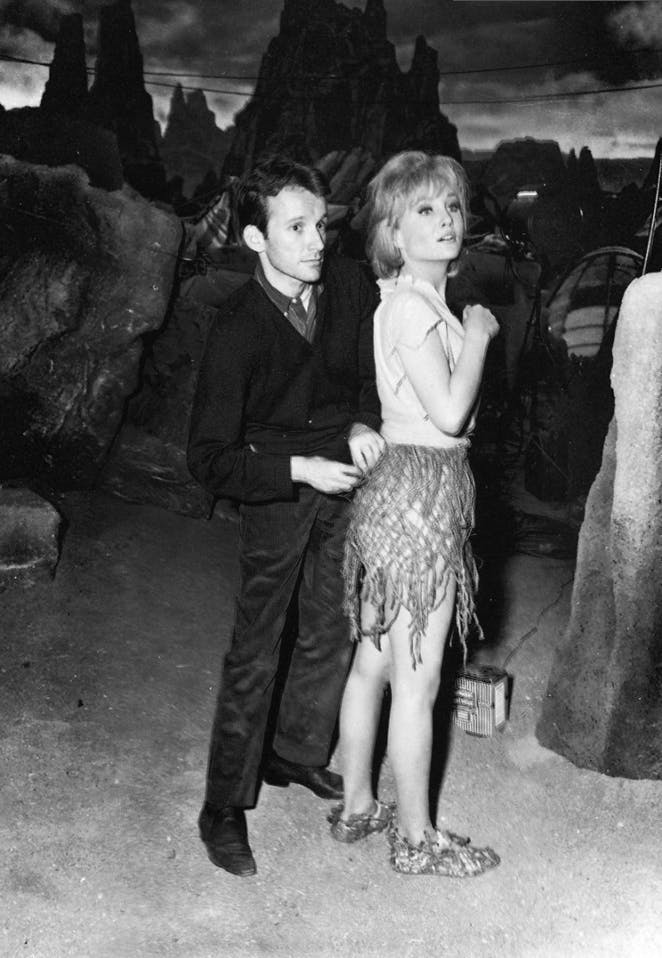

Costume designer William Ware Theiss adjusting Susan Oliver's wardrobe on the set of The Original Series pilot "The Cage"

StarTrek.com

"After Gene saw the play, I was set to do the first Star Trek pilot."

Theiss created a futuristic look for Star Trek by using materials "wrong" side out, employing then-new fabrics like velour and odd materials like foam for landing party jackets. He created uniforms and casual wear, rags for illusory survivors, metallic alien gowns, and sexy yet TV-safe costuming for the iconic green Orion dancing girl.

But Star Trek‘s pilot was rejected so Theiss went back to wardrobe and the occasional costuming gig for series like The Dick Van Dyke Show, Gidget, and The Donna Reed Show. Theiss returned for , which sold, but had to keep working gigs until series production started.

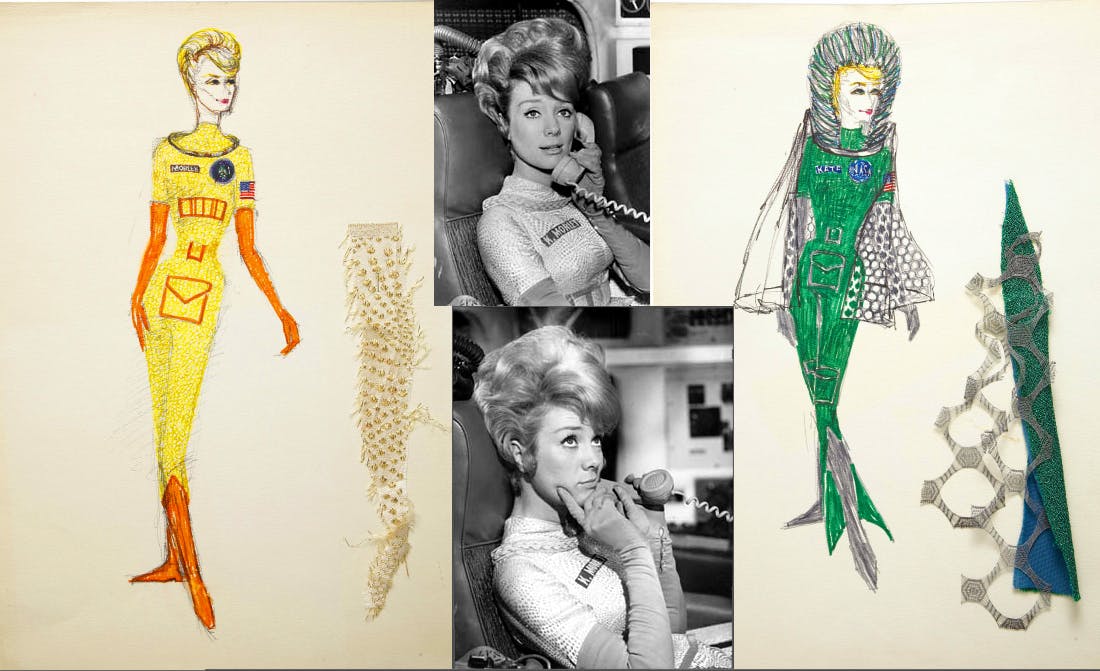

William Ware Thiess' design sketches and episodic stills for the "Katy in a Capsule" episode of The Farmer's Daughter

Screen Gems Television

Notable was The Farmer's Daughter episode "Katy in a Capsule," in which beautiful Inger Stevens dreamed she was the first lady astronaut. "I designed her wild, fantastic costumes, which were great fun, because at the same time they had to be absurd, high fashion, and pseudo-scientific."

Theiss got another chance to stretch his science fiction design muscles for a second Bradbury play called "The Wonderful Ice Cream Suit" (and, during Star Trek’s second season, a third Bradbury show, "The Anthem Sprinter") before shipping off on a three-year deployment aboard the U.S.S. Enterprise.

Beaming Up and Dressing Up the Enterprise Crew

"Charlie X"

StarTrek.com

With Star Trek, Theiss had finally landed his first series gig as a Hollywood costume designer. This initially involved redesigning the starship Enterprise wardrobe.

"The uniforms were a committee design," Theiss complained.

One such "committee" decision was discarding the women's pants in favor of the then-trendy miniskirt. Dorothy Fontana said Roddenberry "wanted sexier uniforms."

"I just didn't think that the women should be in pants.... I think I wanted to look like Flash Gordon," Grace Lee Whitney (Yeoman Janice Rand) told me before her death in 2015.

Short skirts were nothing new to movie and TV sci-fi, but Theiss managed to imbue his form-fitting miniskirts with a flair that made them look passably professional even while absurdly mini.

In addition to her mini, Whitney credited Theiss with Rand's maxi hairdo. "It was composed of two Max Factor wigs woven together over a mesh cone," Whitney said in her memoir. To this author, she said, "We just kept going back and forth to Gene's room, and back and forth, and he kept saying, 'No, higher.'"

"Who Mourns for Adonais?"

StarTrek.com

Most infamous were his designs for "will she or won't she fall out of it" couture for many guest stars.

"He felt that revealing non-sexual flesh (the outside of the leg, off one shoulder, the back) promised that the viewer would see more — but they never did," said Fontana, citing as exemplar the Lt. Palamas (Leslie Parrish) gown for "".

Theiss agreed, telling Fontana, "I feel this design, while Greek in feeling, was a completely fresh idea," describing it as one of his favorites.

Coming Back Down to Earth

Planet Earth

Warner Bros. Television

Then Star Trek was over and seemingly done. However, Theiss never entirely escaped Roddenberry's orbit, costuming the Roddenberry-scripted and produced cinematic bomb Pretty Maids All In a Row, followed by the TV movie/pilot Genesis II and its retooled and redesigned sequel, Planet Earth. For the latter, Theiss designed attractive two-color one-piece jumpsuit uniforms, which prefigure those on .

In Variety, he was announced as "special consultant" on the , likely acknowledging the reuse of his costume designs.

StarTrek.com

Many feature films in the '70s featured Theiss designs, notably the classic Harold and Maude, and 1976's Bound for Glory, for which he received an Oscar nomination. In 1978, he beamed back to the Enterprise for the prospective Star Trek TV series revival, but found his hands tied by a budget-driven decision to keep the uniforms close to those he'd designed in 1966. Despite that restriction, he tried to break loose with alternate tailoring and new leisure wear more modern for the time. But when that TV Trek was canceled, Theiss returned to the big screen.

But months later, the first Star Trek movie started up under director Robert Wise.

"Bill came in from a motion picture location shoot in Colorado where he was working to show Wise his ideas for the movie," said Fontana. "Mr. Wise apparently was not too impressed. Bill shrugged his shoulders and went back to the western he was working. When and Butch and Sundance, The Early Days came up for Oscar consideration, Bill was nominated for Costume Design. Star Trek: The Motion Picture was not. Point made.”

In 1981, he did a special dress design commission for that "smart aleck" friend, Fontana. "Bill designed my wedding dress of blue-grey lace, off the shoulder and cocktail length," she enthused.

Heart Like A Wheel

20th Century Fox

Theiss received his third and final Oscar nomination for 1983's Heart Like a Wheel, but winning a big industry award remained elusive.

The Disney Sunday Night Movies was a Theiss' staple in the mid '80s, and he designed a dozen of them, including a favorite of many children, "Mr. Boogedy."

But in 1987, Roddenberry came calling again for Star Trek: The Next Generation, handing Theiss the chance to do what Robert Wise had not — redesign the future he had created, and set the standard for Star Trek's uniforms from 1987 through the Picard series.

Bill's Big Goodbye

Star Trek: The Next Generation

StarTrek.com

But what was Theiss like?

People who knew him from The Original Series described him as "witty," "talkative," "intelligent and talented," and "a real class act," then — often in the same sentence — added "prickly," "extremely intense," "talented, but difficult," and "rude." Star Trek veteran Robert Justman described Theiss on TNG as "still impatient, still contentious, still very private."

It was for The Next Generation that Theiss finally won an industry award — the Emmy for Outstanding Costume Design for a Series for "." The seeming irony is his Star Trek win was not for 24th Century costuming, but early '40s noir.

What viewers miss, but Hollywood caught, was Theiss wasn't merely using stock 1940s wardrobe, but design for effect, evoking pulp detective fiction by mixing and matching for the best effect without being authentically "period."

StarTrek.com

In the autumn of 1988, Theiss was a guest at a Trek convention in Richmond, Virginia. In attendance, and wearing the uniforms they'd made with the help of Theiss' surprise phone call, were Dennis Russell Bailey and his friend Lisa. They spotted Theiss, looking a little lost, hugging a large paper grocery bag.

They introduced themselves. Theiss set his paper bag down on the carpet and talked with them.

"Finally, a friend asked if Mr. Theiss would take a picture with us," Bailey says. "He agreed and, as Lisa and I took our positions to either side, he said with a slight smile, 'Would you like to have this in the picture?'"

StarTrek.com

"Reaching down into the paper bag at his feet, he brought out the Emmy he'd recently won. We've referred to that, ever after, as the day that we met Bill and Emmy Theiss."

William Ware Theiss left Star Trek behind after the first season of The Next Generation, reportedly suffering from the effects of AIDS. He passed away three years later in 1991, but his iconic creations and the descendants it inspired live on in the 21st Century, and perhaps, beyond.

This article is dedicated to the late Dorothy Fontana, who vetted much of the research.

Acknowledgements

In addition to Dorothy, the author gratefully acknowledges the following for their invaluable help and assistance — Andrea Weaver, Grace Lee Whitney, Michael Kmet, David Tilotta, Dennis Russell Bailey, Richard S. Boswell, Sherilyn Connelly, the San Francisco Clerk's office and the libraries and alumni associations of Lowell High School and Stanford University. Ron and Jennifer Coleman for funding the research. And last but not least, Ryan Thomas Riddle for his insightful notes on the piece.