Published Jun 22, 2023

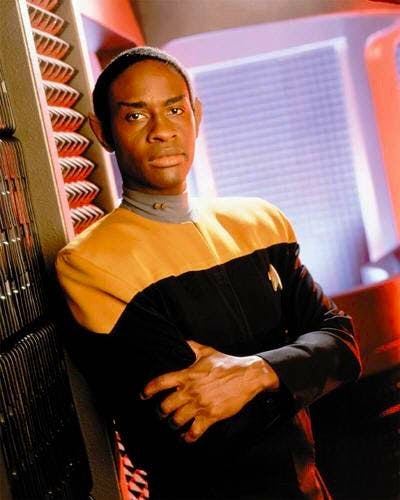

Tuvok Was A Champion of Men's Mental Health

Tuvok feels very deeply, and he knows this about himself.

CONTENT WARNING: This article contains mention of sexual assault and self-harm.

StarTrek.com

In the “Hunters” episode of Star Trek: Voyager, the crew is overjoyed to receive an e-bundle of correspondence from their loved ones back on Earth.

Tuvok, too, receives a letter from his wife and children. Neelix, beside himself with joyful empathy, delivers the message. Tuvok acknowledges receipt – and continues his work. “You’re going to wait until you’ve finished the tactical review,” asks Neelix, dumbfounded. Tuvok stoically confirms that is indeed his intention. And yet when Neelix leaves the room, Tuvok is evidently – if understatedly – drawn to the message. And why wouldn’t he be? He hasn’t heard from his family in over three years. The glance from the console towards the letter is brief and subtle, but significant.

StarTrek.com

You see, Tuvok feels very deeply. We, the viewer, know this. So, too, does Tuvok himself.

Why, then, would Tuvok be so reluctant to show this to his colleague? To anyone, in fact. We’d be forgiven if we took for granted the characteristic ‘unfeeling’ logic of the Vulcan people, thanks to the decades-long presence of Spock and the multitude of stoic Vulcan guest stars across the franchise.

But when we dig a little deeper into the reasons for Tuvok concealing his emotions, and into the unhealthy Vulcan means of handling those emotions, we mere 21st-Century humans might well come to make some very striking, and very familiar, observations.

Most revealing are the flashback sequences in “Gravity,” which show an adolescent Tuvok learning emotional control from a Vulcan Master. Young Tuvok is utterly brimming with feelings, and what’s more, he is infuriated by the idea that he must suppress them at the behest of wider Vulcan society. Why must we fight against the natural expressions we were born with? Emotions, the Master ripostes, are powerful tools — tools that must be harnessed and, ultimately, repressed.

StarTrek.com

The problem here is that, while the Vulcan Master is obviously right to steer Tuvok away from the unreturned passions of his would-be lover – a Terellian diplomat named Jara – he then teaches Tuvok to deal with it, in what we humble Earthlings would deem to be wholly inappropriate and unhealthy methods. Self-control is indeed important, for a man and for those around him. But the Master says that love is the most “dangerous” of all emotions, and that it must, in effect, be ignored. You mustn’t risk speaking your heart only to be rejected for this will result in “shame.” That is — do not communicate how you feel and ignore how you feel, for fear of embarrassment. It is best, he implies, to ignore it all and hope it goes away.

Vulcan society thus teaches both feeling and emotional communication out of young men. The sensations of love and lust are not absent at all in their future lives. In the same episode, Tom Paris confronts adult Tuvok, “You work hard to bury [your emotions], but they’re there.” This woman you’ve met here, he says, when you look at her, you “look like someone who wishes he wasn’t born Vulcan.” If you felt you could admit it, you would.

StarTrek.com

If it isn’t obvious already, I’m explicitly comparing the culturally-enforced suppression of male Vulcan emotion and the subsequent harmful effects this has on subsequent male behavior to the very same culture(s) and behaviors we live in and exhibit today.

Of course, Vulcan isn’t an all-male society, but when we see the ways in which young Tuvok is taught not to express feeling, the ways in which he carries this through into his adult life, and the profoundly flawed and harmful ways in which both Tuvok and Ensign Vorik (see below) deal with repressed emotions, we see an analogy with our male human selves/counterparts. Through the Vulcans, we are perhaps even forced to consider why men in our present-day society refuse to speak of their feelings and emotions (the good and the bad) even when they threaten harm.

StarTrek.com

Men and boys the world over continue to not express themselves. This, I’m sure we can agree, is a widely acknowledged problem even now in the 21st Century. As many (though not all, and this is the problem, really) men can tell you, society insists it is important to “be a man,” to “man up,” and, of course, never ever cry. Such an outward expression of sadness or grief is liable to designate you as effeminate (whatever that really means), “less of a man” (whatever ‘man’ even is), and will embarrass deeply whoever might be around you (it won’t).

Express yourself? No, men are told, it is best if you just maintain silence. Ignore the fact that residing within all of us is a persistent voice that wishes to be heard, one that when permanently silenced, eats away at him and threatens both subtle and explicit harms to him and those around him. Never confess that a hurtful comment harms your feelings. Don’t embarrass yourself by admitting to others that you have a personal problem. And if you’re straight, only ever approach women with an overabundance of confidence verging on entitlement.

How many of us know that these ‘suggestions’ are profoundly wrong? How many of us nevertheless recognize them?

StarTrek.com

See what happens to those (Vulcan) men who are taught in this way, who are forced to keep their emotions silent, and are not provided proper guidance for suitable behavior. What kinds of terrible consequences might occur? Just ask Ensign Vorik (though you’d likely be met with embarrassed silence). In “Blood Fever,” Vorik experiences pon farr and makes lustful advances towards B’Elanna Torres. She rebuffs him repeatedly; but to Vorik, "no" means "yes." He even forces a mind-meld upon her – which is, in effect, sexual assault. B’Elanna fights him off, though she should, of course, never have been put in that position in the first place.

Vorik is mortified when he must eventually explain himself, although he struggles to even appreciate what he has done and why. Tuvok is visibly uncomfortable when approached to assist. He is of very little help, despite being the only other (certainly senior) Vulcan aboard; and when he does finally offer Vorik his help, Tuvok is uncharacteristically overly apologetic. This is because – and both Vulcans make this clear – pon farr, being a sexual process that elicits very strong, otherwise ignored feelings, is never spoken about in public. It is far too embarrassing for a man to acknowledge another man’s problems, even if it ends up being a detriment to women or himself.

StarTrek.com

The Doctor claims this to be a “Victorian” attitude to mating — but in witnessing the combination of both the socially-sanctioned suppression of emotion we saw in “Gravity” and the violent emergence of bottled-up feeling present in “Blood Fever,” we might be inclined not to see this behavior as a thing of the past. Not for the Vulcans – and perhaps not for we humans either.

It may seem as if I’m being unduly harsh on the ways some men are reared, but these analyses aren’t without reason. Year upon year, crime statistics in the UK demonstrate that male sexual assault perpetrated against women is a persistent issue, and that many instances of these are committed against minors by boys who haven't had proper sex-education in the matter of consent. Some psychologists believe that men "lashing out" at women is more about fear than sex, that the only "acceptable" outlet for handling difficult emotions is to act out in anger. But surely one reason for this hideous lack of respect for women’s autonomy might reside in the way we teach boys about girls? And, surely, in the way we teach boys about themselves?

Consider that, in the UK at least, consent wasn’t on the school sex education agenda until well into the 2010s. Then put that into the wider cultural context in which men and boys (UK and elsewhere) operate. It is not hard to see how a male-centric global society such as ours infiltrates the minds of the young. The men of both worlds need to learn to know themselves, and to respect others. So, the boys of present-day Earth might therefore do well to have their own Vulcan Master teaching them to respect a young woman’s rebuff (as in “Gravity”), even while they might need to quit his lessons before he got on to ‘How To Pretend You Don’t Have Any Feelings At All 101.’

StarTrek.com

Our principal issue (only for the purposes of this article, not for the broader issue of assault) is in how this could all have been stopped if Vorik had understood what he was feeling and doing, and if Tuvok was able in the first instance to assist by talking to him. That B’Elanna was attacked in the first place is due to the fault of the attacker, Vorik; the embarrassed reticence of his Starfleet and Vulcan ‘mentor figure, Tuvok; and of the wider Vulcan society that oppressed the two of them in the first place, as seen in “Gravity”.

And at the center of this is the inability to communicate, an opposition to the notion that emotions are perfectly natural provided we know how to handle and express them properly. The secrecy intrinsic to the pon farr in Voyager makes it harder for Vulcan men to understand what is and is not acceptable, and the wider fact that Vulcans are taught from an early age to suppress and disregard emotion forces them to pretend they don’t exist or are not a threat.

StarTrek.com

This is not in any way to excuse or defend those men who perpetrate violence against women in the real world (or on-screen). I suggest instead that providing clear and consistent advice to boys in their formative years might well prevent their acting irresponsibly and harmfully to women and girls. The data suggests that educating boys in what is and is not right – rather than ignoring the thorny issue of action – decreases rates of assault. Certainly some clear communication, from education to interpersonal conversation, may have helped shape Vorik (and Tuvok) into healthier, positively expressive individuals.

To me, the Vulcan way of doing things appears eerily like the 21st Century’s own methods of ‘educating’ men — Get them when they’re young. Ensure they never show their true feelings. Suggest that the eruption of bottled-up emotions (here, pon farr) is a more-or-less natural part of life ("boys will be boys," perhaps?) instead of facing up to it and challenging it. Eventually, distance yourself from everyone around you until you blow up.

Yet Voyager also shows us an exaggerated version of what men could be if they weren’t tied down by such constraining gender norms. In the episode “Riddles,” an alien attack disrupts both Tuvok’s memory and his emotional stability. It is implied that his cognitive reasoning is affected, and that he loses self-control; but it would be more accurate to say he loses the barriers that prevent him from showing those emotions. It is perhaps unsurprising that, given the ability to do and say as he feels, this Tuvok is a very pleasant fellow (if a little childlike in temperament). An unguarded Tuvok is able to play, to make things, to become actual friends with the crew. Even Neelix! Without the cultural and social baggage, Tuvok would be an expressive individual who still retains the brilliance and talent that makes him such a valuable officer on Voyager.

StarTrek.com

Although the apparently super-restrained Tuvok can deal with his usual repressed emotional state well enough for the most part, we regular men of 21st-Century Earth perhaps cannot. Statistics and figures the world over, from the US to the UK to Japan and everywhere in between, reveal that with each passing year comes an increase in men and boys’ self-harm and even suicide. This, of course, is because of the very strictures we place on them to "toughen up," to not speak, to "not be weak," and to avoid empathy.

As I understand it, and in seeing these two episodes as Vulcan analogies for very real problems, there are two likely outcomes for men who bottle up their feelings and refuse to communicate the mental and emotional issues they face — they will become depressed and thus risk bringing harm to themselves (whether feeling like they must live unhappy lives, or worse), or they will lash out when it all becomes too much, thereby harming others.

Despite the obstacles, however, well-adjusted, self-aware men can be wonderful. Tuvok, too, can also be utterly lovely. Most Voyager fans like Tuvok — on a more regular day, he is intelligent, quick-witted, loyal, and deeply respectful of his friends (especially Janeway). Let’s not forget that Tuvok is an excellent dad.

StarTrek.com

In “Innocence,” he is forced to look after three children (or so we think). While he is often exasperated (children are often exasperating), he is also responsible, sensible, protective, brave, and assertive without being unkind. He describes in this episode how he is able to live “without emotion,” yet still love his wife and his own children; they are a part of his very soul, they mean more to him than any identifiable emotion.

This is much closer to the Tuvok I want to be. And while Tuvok, Vorik, and the Vulcan Master often show us how men can think and act when at their worst, in doing this, they might allow us to reconsider what we both do and don’t want to be.

This article was originally published on March 3, 2021.