Published May 23, 2023

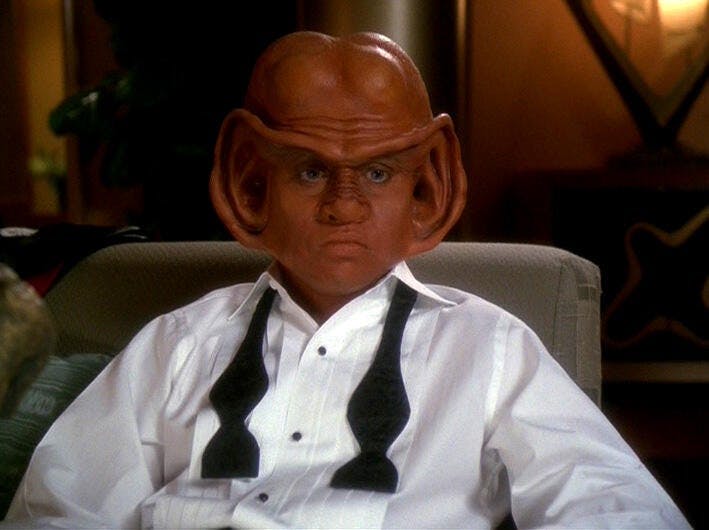

Nog and the Post-Traumatic Progress of Star Trek Characters

The authentic PTSD journey seen in 'It's Only A Paper Moon' allowed for richer mental health representation in the stories that followed.

StarTrek.com / Rob DeHart

In December 1998, Paramount Pictures and Syndication aired Star Trek: Deep Space Nine’s 160th episode, “It’s Only a Paper Moon.” Unlike many of the stories told about this far-off future, there was no terrorist threat, wormhole collapse, or other science fiction calamity. Instead, the entire episode centered around the traumatic emotional journey of one character — Nog.

StarTrek.com

The childhood best friend of Jake Sisko was a staple of Deep Space Nine. While not a main character, he was involved in many plotlines, often right by Jake’s side. Despite his stereotypical beginnings as a greedy Ferengi troublemaker, Nog grew quite a bit over the seasons, eventually becoming a responsible, idealistic, duty-bound Starfleet cadet. Jake, the Starfleet officers around him, and his father’s own journey of self-worth completely changed his life’s trajectory. But nothing in Nog’s life ever changed him quite like “The Seige of AR-558.” During this iconic episode, over a 150 Starfleet officers engaged in combat with the Jem’Hadar.

StarTrek.com

While Nog survived the gruesome battle, he lost his leg. Physically, replacing the limb was simple for Starfleet Medical; they’d give him a hyper-realistic prosthetic and he’d be back to working order in no time. He’d just need a bit of rehab first. In most Star Trek storylines, that’s where Nog’s disabled journey would end. Fans might hear mention of his prosthetic every so often, but Nog would return seamlessly to his role as an eager Starfleet cadet.

But that’s not what happened.

StarTrek.com

Instead, when Nog came home in “It’s Only a Paper Moon,” he is a shadow of his former self. He can walk, and he can function physically, but he’s not well mentally. In a handful of heartbreaking scenes, the episode makes it clear that he’s struggling with readjusting to Starfleet, his family... His entire life. He gets flashbacks to losing his leg and suffers phantom pain, a common phenomenon in amputees. He sleeps for endless hours throughout the day and the only thing that seems to comfort him is a Vic Fontaine recording of “It’s Only a Paper Moon,” a song fellow officers at the siege played to boost morale. And the condition that has him bouncing back and forth between reality and the Siege of AR-558 is PTSD.

PTSD (or Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder) is a mental illness that occurs after experiencing or witnessing a particularly terrifying incident. It’s commonly found in survivors of tragic events (shootings, car crashes, assaults, and combat). It’s characterized by:

- Recurring, vivid memories and flashbacks to the event

- Nightmares and sleeplessness

- Avoidance

- Negative changes in thinking and/or mood

- Intense physical and emotional reactions such as anxiety, fright, anger

Despite being a franchise all about space explorers who often end up in traumatizing scenarios, few Star Trek characters explored this mental illness with the authenticity and depth it deserved. Not until Nog.

StarTrek.com

Star Trek’s history with mental health throughout the 1960s-2000s has been a bit complicated. While the show’s approach to mental health has always been somewhat progressive (adding counselors as necessary crew members as early as the '90s), the long-term care put into writing characters’ mental health journeys has been a bit scant. For example, until Lieutenant Barclay, Deanna Troi’s work as a psychologist and counselor was limited. We’d see her sessions in one episode, but there was little follow-through with any long-term psychological care. Consequently, the majority of her counseling was either with one-episode characters in full crisis or vague mentions of sessions off-screen.

Later, Star Trek: The Next Generation does evolve Counselor Troi’s work to include long-term cases. Both Lieutenant Barclay and Worf, as well as his son Alexander, are great examples. However, even those episodes that revisit her therapy sessions center on sci-fi hijinks. After all, Barclay’s teleporter phobia was complicated by him actually seeing space worms, and Worf and Alexander’s troubled bond took a backseat to the holodeck Wild West town filled with Datas (“Realm of Fear,” “A Fistful of Datas”). As was common in much of the '90s-era Star Trek, a character’s long-term psychology was considered and written into their stories, but it played second (if not third or fourth) fiddle to the episodic, wacky sci-fi crisis of the week.

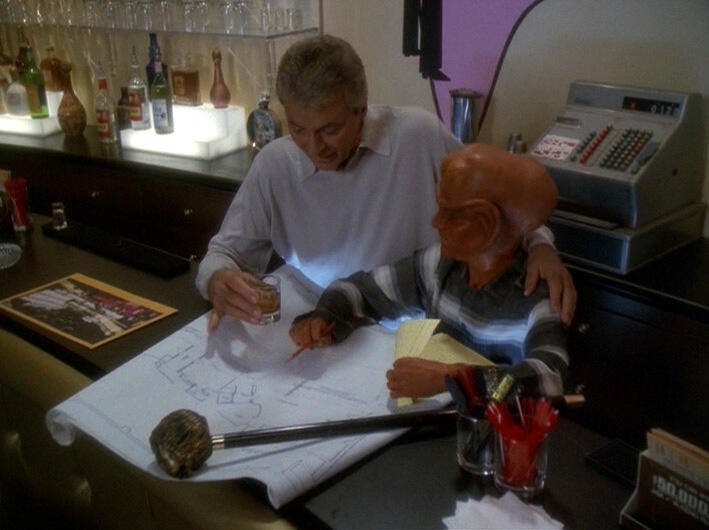

Vic Fontaine - Star Trek: Deep Space Nine's Most Famous Hologram

Other times, Star Trek avoided the space worms and cowboy Datas to take a hard look at the deep psychological horrors these officers can face. Unfortunately, the franchise often struggled to give those challenges ample repercussions. Most famously, in the Deep Space Nine episode “Hard Time,” Chief Miles O’Brien experienced 20 years in prison in a matter of hours. The experience understandably haunted O’Brien. He struggled with remembering his old job, suffered intense stress, anxiety, and fierce rage, and even saw hallucinations of his fictional cell-mate (one that, in his horrific 20-year VR trauma, he killed for food). He was afflicted with irritability, frustration, and depression. He even tried to take his own life. By the end of the episode, his friends must talk him off the edge, then help get him medication and counseling sessions. O’Brien hugs his daughter as the screen fades to black and then... it’s never mentioned again.

After his time in jail, O’Brien was driven to extreme violence, hallucinations, and self-harm. Most people would be in therapy for years trying to unpack all of that, if not placed in hospital care for a while to readjust. But when fans see the next O’Brien-centered story, it’s 12 episodes later, where O’Brien is dealing with the typical “O’Brien family marital troubles” and having to sabotage Deep Space 9 to stop a ghostly alien from killing Keiko. You’d think he’d have more of a crisis about doing criminal activity given what he went through, but it’s as if the whole thing never happened.

Nog’s story is markedly different from stories like Barclay’s, Worf’s, or O’Brien’s. Not only does the episode lack a lot of the sci-fi plot added into the other mental health episodes, but it also doesn’t happen in a few days and isn’t forgotten. Instead, we follow Nog through weeks of recovery, self-discovery, and progress with his conditions. The story of “It’s Only a Paper Moon” is about Nog’s PTSD, realistic and raw, and that’s enough.

StarTrek.com

“It’s Only a Paper Moon” is strengthened as a story because of how authentic the writers made Nog’s PTSD. Throughout the episode, Nog employed real tools used by modern PTSD survivors to process their condition. For example, the writers had Nog participate in creative therapy. Creative therapy is the process of using artistic mediums to learn how to heal the painful, wounded parts of your mind and slowly re-acclimate and reconnect to the world around you. Psychologists and doctors have been using this tool for decades to help people with PTSD cope with their condition. In Nog’s case, he first clung to the one coping device he had, which was listening to Vic’s music to help him escape from the trauma. It reminded him of his lost friends, and the version of himself he lost in "The Siege of AR-558," too. Creative therapy only helps Nog more once he starts working with Vic. In designing a bigger and better casino for the holosuite, Nog gets to have a creative outlet. He finally could make enough space between himself and those difficult feelings of loss, guilt, and grief to build something out of that emptiness.

Another authentic, powerful part of the episode's storytelling is Nog’s recovery process. The writers of "It's Only A Paper Moon" don’t make his process a predictable, one-dimensional, linear experience. It’s a common mistake in mental health portrayal to act like once someone starts getting help, they’ll be fixed forever. But it’s not that easy. At first, Nog gets better physically from his injuries but lags mentally. Then, he begins working with Vic and seems to be much better. But when suggested to leave the holosuite, Nog regresses and closes off from his loved ones again. He may always be working to get better, but some days are better than others. That’s what real mental illness recovery looks like.

StarTrek.com

Related to that regression in the holosuite, the episode also fits in time to discuss the pitfalls of some PTSD coping mechanisms. In Nog’s case, he clings to the improvement he experiences while in the holosuite. But that “ideal” involves staying in that holosuite for the rest of his life. While creative outlets help people with PTSD get out of their own heads, that comforting escape can turn into uncontrollable, unhealthy escapism. Escapism helps trauma survivors, but if done too often, it can turn into an addiction that leads to avoidance of their real life. Then, different methods are necessary to help them take the next steps forward (like disconnecting the holosuite and starting sessions with Ezri).

As an episode, “It’s Only a Paper Moon” takes the time to let Nog go through every stage of his trauma, stress, and loss. He escapes, he rebuilds, he grieves, he processes. He hurts and avoids people he loves, he accepts what happened to him and opens up about all the pain that he feels. In the end, he isn’t perfect. He still has a long way to go. But he’s begun his journey back to himself and that’s what matters.

And Nog’s story doesn’t end there.

StarTrek.com

Nog’s life after “It’s Only a Paper Moon” is almost just as important to viewers, if not more. Representation in media is one of the top ways to help people not only see themselves reflected in the world but also get a glimmer of who they could become. In Nog’s case, he goes through counseling and comes out stronger because of it. Then, he goes back into Starfleet, and not only excels at his work, but also becomes the first Ferengi captain. He is loved, important, and excellent. That’s so much more than most people with PTSD are told they can have. Unfortunately, many mental health stories lead to a character having to settle for a quiet life. But Nog got to be more than that. He wasn’t some broken person who could only scrape by with a smaller, lesser life. He lived a fulfilling, thrilling life and changed the face of Starfleet, trauma and all. The writers chose to let Nog live excellently, disability and all.

And because of that choice, Star Trek was gifted with an authentic experience of mental disability that inspired dozens of stories after it.

StarTrek.com

Once Star Trek wrote about Nog’s authentic PTSD journey, the topic became an open conversation with all other Star Trek characters. Now, it’s common for the shows to integrate storylines that analyze and explore the trauma-related psychology of its characters. Sometimes, it even becomes the focal point of a series. Star Trek: Picard has been a multi-season adventure in unpacking the admiral’s lifelong traumas, from his Borg experience to losing Data, and even his unprocessed grief from his difficult childhood. Ever since Nog proved that Star Trek fans can be compelled by long-term psychological care and its effects on a character, it’s become a staple of the newer series. Alongside Burnham, Culber, Pike, and many others, we’ve been allowed to see these characters’ emotional journeys. And nowadays, these journeys rarely end when the credits roll; the trauma that each Star Trek character faces evolves throughout multiple episodes, letting us appreciate the nuance of each of their lives.

While mental health representation is still lacking in the modern world, Star Trek is doing its part to push boundaries and let its characters grow in a hopeful, mental health-forward future. Without Nog’s story taking that first step, we’d never have gotten here at all.