Published Aug 13, 2024

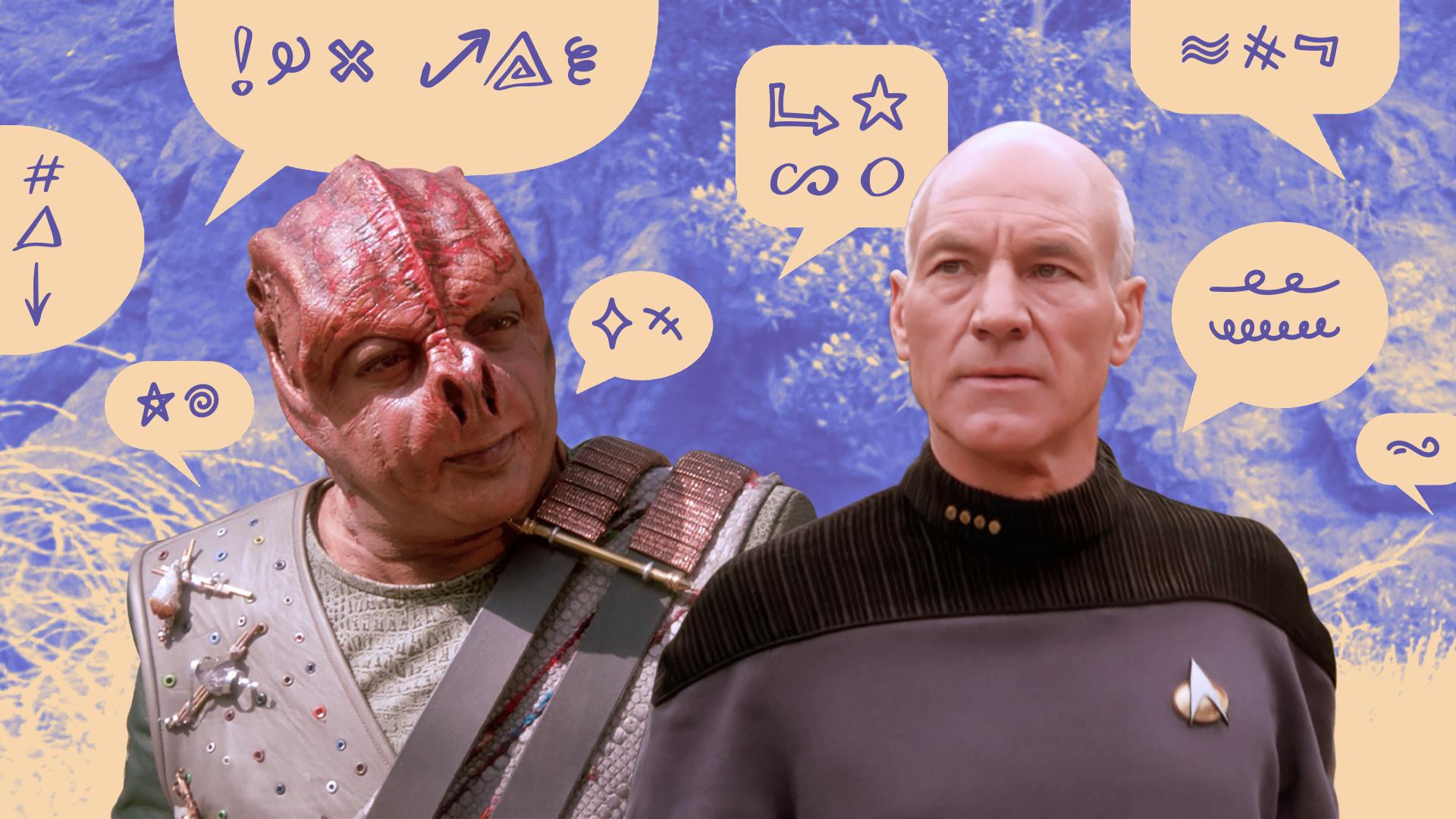

Striving to Create Our Own 'Picard and Dathon at El-Adrel'

The Next Generation's 'Darmok' has lessons to teach us, still.

StarTrek.com

In the second episode of 's fifth season, "," the Enterprise is on-route to the El-Adrel system to make contact with a race called the Children of Tama. Although the race has been peaceful, a failure to communicate pervades — the Children of Tama's language is seemingly indecipherable.

"But are they truly incomprehensible," Picard asks the officers on the bridge as they set a course for the El-Adrel system. "In my experience, communication is a matter of patience, imagination. I would like to believe that these are qualities that we have in sufficient measure."

It is this attitude that separates the Enterprise crew from the "" stories between European explorers and the native inhabitants of North and South Americas in the 15th and 16th Centuries here on Earth. Instead, Spanish Conquistadors such as Hernán Cortés entered these "new worlds" with the intent to conquer rather than communicate.

"Darmok"

StarTrek.com

At first, the Enterprise believes this may be the case with the Tamarians. After the Enterprise hails the Tamarian ship and the two captains attempt to communicate, Picard's mouth straightens into a line, his signature "this-is-not-going-well" expression. The Tamarian captain argues with his bridge crew, takes a dagger from one of his officers, and, now holding a weapon in each hand, addresses the crew with, "Darmok and Jalad at Tanagra." Abruptly, the two captains are beamed to the surface of the planet El-Adrel IV below the ships.

Unable to transport Captain Picard back due to a particle scattering field on the planet's ionosphere created by the Tamarian ship, Commander Riker asks Security Officer Worf his read of the situation. "It is a contest between champions, perhaps," Worf replies, channeling his Klingon sensibilities. In his culture, this is how an analogous situation would play out.

Meanwhile, the two captains struggle to understand one another on the plant. Picard thinks the Tamarian captain wants him to take the knife for a fight and keeps refusing it even as the Tamarian continue to insist he take it. Night falls and no progress has been made.

"Darmok"

StarTrek.com

The first moment of clarity, when Picard begins to understand, happens when the Tamarian captain, seeing Picard cold that night on El-Adrel IV's surface, tosses Picard a flaming branch for warmth. He pairs the gift with the phrase, "Temba, his arms wide."

"Temba is a person," Picard realizes. "His arms wide because he's holding them apart, in generosity. In giving. In taking.”

It's a genuine moment of language exchange and acquisition, part of the Tamarian captain's plan all along — through shared experiences, the two races would be able to gain a common vocabulary. Picard's words serve as a metaphor for the process of language learning, and also hint at the key to understanding the Tamarian language — metaphor.

It is also a moment of charity — of gift-giving to aid Picard in an unfamiliar, foreign place. This scene is pivotal; isn't generosity just the culmination of the characteristics Picard referred to before — patience and imagination?

"Darmok"

StarTrek.com

During the 1527 Narváez expedition, Spanish explorer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca spent eight years traveling across the U.S. Southwest, interacting with different native cultures and even acting as a faith healer and trader. His generosity and attitude toward the native populations was an outlier among the Spanish explorers who tended to be conquistadors, entering with the intent to claim, rather than explore. One of these seminal conquistadors was Hernán Cortés.

Shortly before de Vaca, Hernán Cortés marched into Mexico in 1519 and laid claim to everything. Instead of bothering to learn the language of the land, he used a shipwrecked priest and took an indigenous mistress to facilitate all of his orders.

The remaining Bridge crew, unable to understand the Tamarians but unwilling to throw out all attempts and take the forceful Cortés route, instead try to find ways to bring Picard back onboard the ship. The Tamarian vessel thwarts each of the Enterprise's efforts because the crew understands "Darmok and Jalad at Tanagra." They know what the captain is attempting to do.

Picard begins to understand the Tamarian captain is using allusions or references to communicate. The metaphors serve as analogous situations and insinuate the next move that should be made. The generosity of the Tamarian captain has facilitated the beginning of understanding. This comes to a head the following day after a common foe emerges in a creature native to El-Adrel IV.

"Darmok"

StarTrek.com

Just as Picard figures out the Tamarian speaks by "citing example," the Enterprise attempts to beam out Picard, causing the Tamarian captain to face the beast alone. Subsequently, he is gravely injured. After Picard is released from the grasp of the teleportation beam, he cares for the wounded Tamarian who still works to teach Picard his language. As he lies dying, the Tamarian captain is more concerned at bridging the language barrier than conserving his energy. For him, the ability to communicate supersedes life itself.

He urges Picard to share a story from his culture.

Perceptive as always, Picard deduces "Darmok and Jalad at Tanagra" must be the myth of a friendship forged by two people poised as adversaries. He shares the 1800 BC Sumerian myth of Gilgamesh and Enkidu. In the Sumerian myth, the two enemies Gilgamesh and Enkidu come together to fight a common foe and become brothers in arms. When Enkidu is eventually killed in battle, Gilgamesh mourns. The parallels between not only the Tamarian myth but the current situation are not lost on either the Tamarian captain nor Picard.

"Darmok"

StarTrek.com

An oft overlooked aspect of Earth mythologies are their commonalities. In the Gilgamesh epic, Gilgamesh encounters Atrahasis, the lone survivor of a great flood the gods inflicted to restart humanity. To survive, Atrahasis built a large ship. If this sounds familiar, it's a story that also appears in the Bible, of Noah and his ark. But it also appears in Greek mythology as Deucalion, the son of Prometheus, sailing in a chest or ark for nine days to survive a flood that destroyed humanity. Ancient Aztec myths told of a couple that survives a large deluge by hiding in a hollow vessel. In the Incan mythology of South America, a great flood Unu Pachakuti kills the first creations of their creator god after he has deemed them inadequate. His second attempt was humanity. One version of this tale has a man and woman escaping Unu Pachakuti by floating in a wooden box.

This is only one salient commonality among Earth mythologies and religions — a flood myth 'rebooting' humanity. Instead of using the commonalities among their cultures as a bridge to understanding, Spanish Conquistadors insisted their version of events were the gospel truth. Hernán Cortés forced the indigenous people he encountered to convert to his system of belief. What could have been a shortcut to understanding was instead used as a tool of oppression.

"Darmok"

StarTrek.com

By the end of the "Darmok" episode, Picard returns to the Enterprise and is able to communicate to the Tamarian crew what happened on the planet's surface, including the demise of their captain. After making religious gestures akin to last rites, the Tamarian first officer says, "Picard and Dathon at El-Adrel." The tale of Picard and the Tamarian captain crossing the language barrier is now part of the Children of Tama's lexicon.

Nearly all of Earth's religions and mythologies contain stories of male friendship, travels into the underworld, deluge myths, and analogous gods and goddesses. If cultures looked at their commonalities as bridges instead of focusing on the differences, a connection such as the one forged by the end of "Darmok" may be possible.

As Picard points out to Commander Riker at the episode's end, "Now the door is open between our peoples. That commitment meant more to [the Tamarian captain] than his own life." We too, here in the 21st Century, could stand to be that committed to communication across cultures.